Essay on the “Rosewood” (Rosenholz) files—microfilmed database of Stasi agents in the West acquired by CIA after the Berlin Wall fell (Der Mauerfall)—and Markus Wolf’s elaborate coding system that took CIA years to crack before they could identify his spies in US and Europe.

Introduction

Markus Johannes Wolf (1923–2006), headed Hauptverwaltung Aufklärung (“Chief Directorate of Reconnaissance”), or HVA, the foreign intelligence division of East Germany’s Ministerium für Staatssicherheit (MfS), known as “Stasi.”[1] Wolf was known as “the man without a face” because he avoided media; the only photo in CIA’s possession was from when Wolf covered the Nazi trials at Nürnberg as a 22- and 23-year-old journalist. For most of the Cold War, West German intelligence (Bundesnachrichtendienst: BND) did not have a recent picture of him. In 1979, a GDR defector identified Wolf from photographs in BND’s possession. A biography and analysis of Wolf’s career is by Kristie Macrakis.[2] Wolf wrote an autobiography,[3] but any autobiography, especially by a man whose profession calls for deception, should be utilized with caution. As Wolf said, history should not be written only by the winners. Wolf had a story to tell.

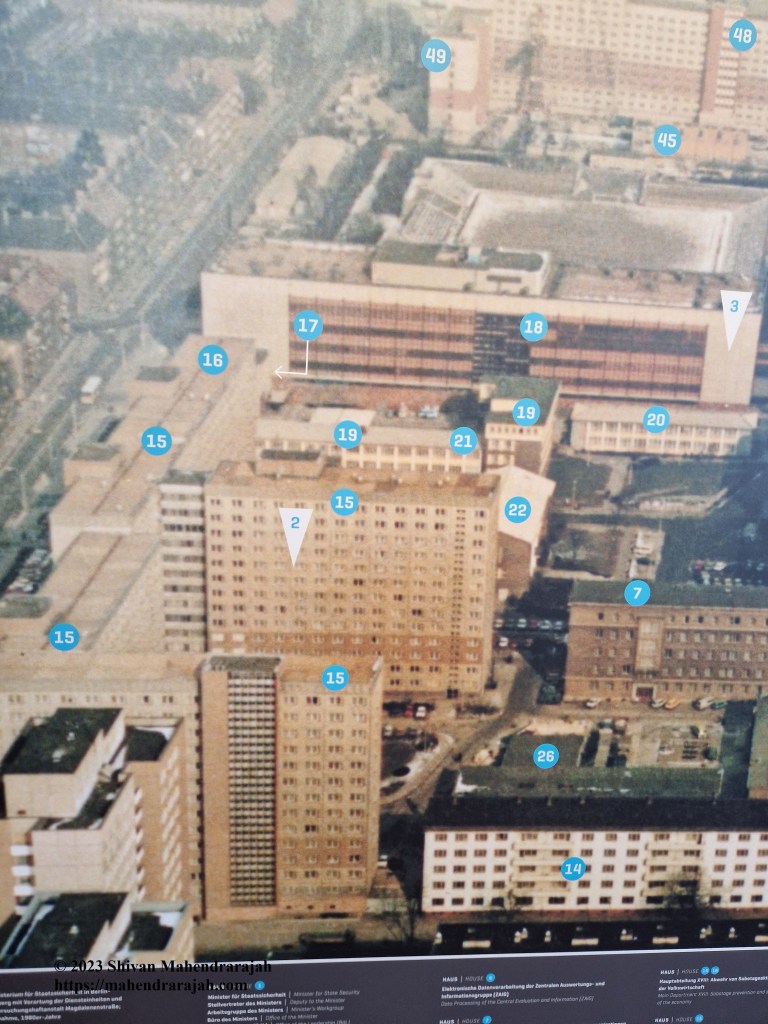

Stasi HQ

The site of the Stasi HQ in Lichtenberg, East Berlin, includes the Stasi Museum, archive, “Campus for Democracy”and sealed buildings. The map below should orientate general readers. The site is huge. Building No. 1 (Museum) is open to the general public. The museum’s contents are banal (as are the tours offered in English and German to unsuspecting tourists), and hold mostly shlock to entertain tourists. The focus of the museum, not surprisingly, is on Stasi’s domestic spying. HVA’s buildings are closed; and artifacts, and documents of interest to historians of Cold War espionage are controlled by the German Federal Archives.[4] When I last visited the Normannenstraße site (2023), I got the sense the towers, especially those that had housed HVA, were headed for conversion to apartments.

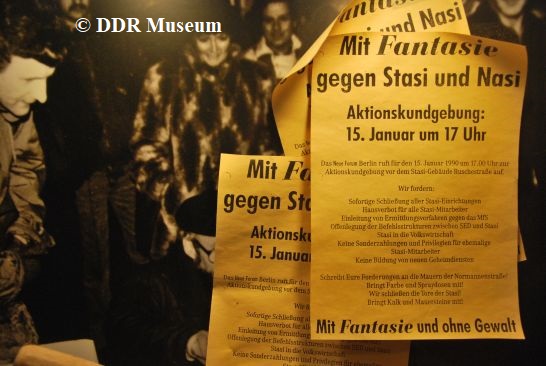

Raid on Stasi HQ

On 15 January 1990, CIA and BND raided Stasi and HVA offices when East German crowds breached the Normannenstraße gate. The breach was not entirely spontaneous; posters had been published calling for action: Aktionskundgebung: 15. Januar um 17 Uhr (“Action rally: January 15th, 5 p.m.”). BND and CIA were ready and went inside by mingling with the angry crowds.

The raid is well-known. BND broke into Stasi’s counter-intelligence offices in Building No. 2. CIA (allegedly) went into Markus Wolf’s office, Room 980, Building (Haus) No. 2, Ruschestraße 104. The office was classily decorated: wood paneling and spacious; private bathroom, shower with expensive blue tiles; and uninterrupted vistas through armored glass. Wolf was supposed to have retired, but evidently kept his hand in the game; hence the office. This is not surprising; he will have handled agents that would have insisted on continuity for their own security and peace of mind; and stayed on top of operations that he had initiated during his tenure.

CIA and BND collected a good deal of information during the raid, but the microfilms, later called “Rosenholz” by BND (in ca. 1993),[5] were not part of this haul.

Rosenholz

In 1985, Erich Mielke, the Stasi chief, ordered the microfilming of ca. 317,000 personnel file cards, many containing real names of HVA agents, along with ca. 77,000 cards with codewords and select details of HVA operations. The earliest record is 1951; the last, 1988.

The Rosenholz Files came into the possession of CIA in 1992, according to public sources, “in unclear circumstances.” The circumstances are clear but classified. CIA propagated cock-and-bull stories to obscure the origins of the files. The microfilms, which were in fire-resistant steel containers, were transferred to about 380 CD-ROMs.

Markus Wolf’s System

The Soviet Defense Minister, Andrei Grechko (d. 1976), used a politically-incorrect term to describe Wolf: “the crafty Jew.” Wolf was indeed quite crafty. The system he utilized to complicate efforts to unmask his agents is brilliant.

Erich Mielke wanted a unified file, but Wolf resisted. He also realized that computers can be penetrated. Rightly so, as we know today, from the manifold hacks of secure governmental, healthcare, and financial databases. A unified index card and computer database with an agent’s information will make it fairly easy for counter-intelligence services to identify moles. Wolf insisted on an index card system (nothing electronic), and broke up the data into three distinct sections; each section was relatively meaningless by itself; the three sections plus each unique record identifier were required to even begin identifying an agent. The records were stored separately, so, if, say, part 1 of 3 of a mole’s record was stolen, it was insufficient without corresponding parts 2 and 3.

- Formblatt-16 (F-16) index cards: they have the true names, addresses, professions, and so on of persons of interest to HVA. Each F-16 card has a HVA registration number. F-16 cards cover considerable ground. The majority of entries are not about agents. The cards are literally about “persons of interest.”

- Formblatt-22 (F-22) cards: they contain limited biographical data, cryptonyms, and HVA registration number.

- Statistikbögen (Statistical Sheets): they have the cover names, dates of birth, etc., and the HVA registration number.

With Wolf’s system, you need the three sets—F-16, F-22, Statistical Sheets—to unmask agents. The HVA registration number is the key to unlocking information in the three sets. But even with the Rosenholz files available to CIA, it took them awhile to crack Wolf’s system.

Conclusion

Wolf was a clever little bugger. He was educated in Russia and spoke Russian fluently. MGB (and later KGB) groomed him from youth; they saw him as “our man” in GDR. He played the spy game brilliantly and professionally; he ran circles around the best that CIA, BND, and SIS threw against HVA.

Given the pikers that CIA has dealt with in the post-9/11 era, CIA case officers who were lucky enough to play the “spy game” against giants like Markus Wolf are surely drowning in nostalgia.

[1] A good resource on Stasi is John O. Koehler, Stasi (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1999).

[2] Kristie Macrakis, “Markus Wolf: From the Shadows to the Limelight,” in Spy Chiefs: Intelligence Leaders in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, eds. Paul Maddrell, et al. (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2018), vol. 2, pp. 145–165.

[3] Markus Wolf, with Anne McElvoy, Man Without a Face (New York: Public Affairs, 1997). The German edition (written without Anne McElvoy) has additional information. Markus Wolf, Spionagechef im geheimen Krieg: Erinnerungen (Munich: List Verlag, 1997).

[4] The Bundesarchiv offers finding guides for files on Stasi’s domestic and foreign espionage. Whether you get access to them or not is an open question.

[5] On Rosenholz, see Bernd Schäfer, “Stasi Files and GDR Espionage Against the West,” IFS Info 2/02 (2002).

You must be logged in to post a comment.