Deaths of Iranian generals in the Iran-Iraq War (1980–88) and war against ISIS (2014–18) prove that Iranian Army and IRGC generals lead from the front. Whereas U.S. generals lead from behind: Vietnam (11 KIA); Iraq (0); AFG (1: REMF, killed in the rear).

On 13 June, when Israel murdered almost two dozen generals, Iranian Armed Forces swiftly re-grouped and retaliated. The Iranian military is accustomed to losing generals in action and has planned for losses.

Introduction

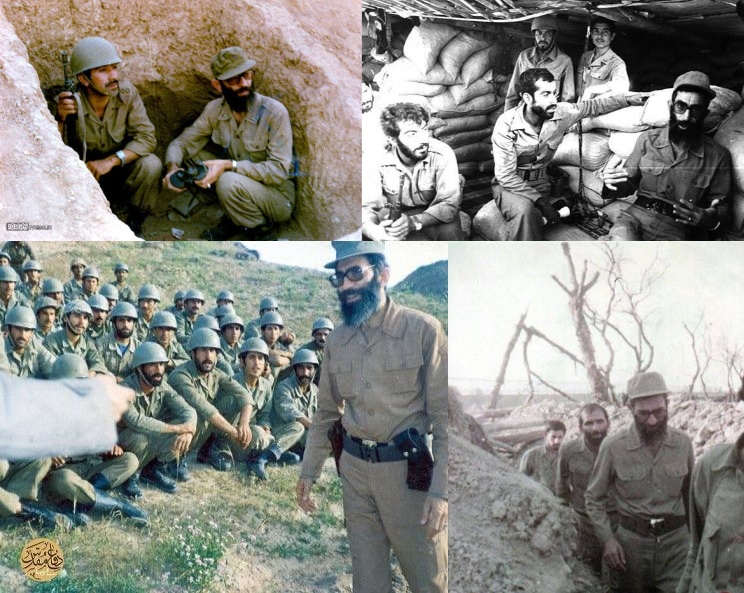

Iranian generals lead from the front, as evinced by the heavy casualties they suffered (see Fig. 2). Their deaths have little to do with any perceived “Shiʿa martyrdom complex” (see Appendix I, below). Deaths reflect leadership style: at the front with the “boys.” American generals lead from the rear, and enjoy exceptionally low casualty (KIA) rates relative to inferior ranks. Soviet staff officers went into hostile territory in the Afghan War (1979–89), and lost about ten generals.

In the Vietnam War (1961–75), U.S. lost eleven generals (Army, 8; USMC, 1; USAF, 1; National Guard, 1); Iraq War (2003–11), zero; Afghanistan (2001–2021), one (Hal Greene, a REMF killed in an insider attack while touring a military academy). I address American generalship in the GWOT in a forthcoming essay, “American Generalship: Leading from the Rear.”

Iranian Generalship

Many of the generals who died in or survived the Iran-Iraq War were young men when they assumed command. They were promoted for diverse reasons: loyalty to the Islamic Republic; to fill leadership voids created by defections of the Shah’s generals; extensive purges; and deaths of generals in a plane crash (29 Sep. 1981). Post-revolution, Iran was in disarray. This was reflected in its Armed Forces. Saddam took advantage of social-political chaos to launch his invasion on 22 Sep. 1980.

IRGC was entrusted to Mohsen Rezai (age 27; IRGC Cmdr., 1981–88), with Ali Shamkani (age 26; 1981–88)—who Israel tried to murder on 13 June 2025—as his second-in-command. Both exhibited audacity and courage on the battlefield.

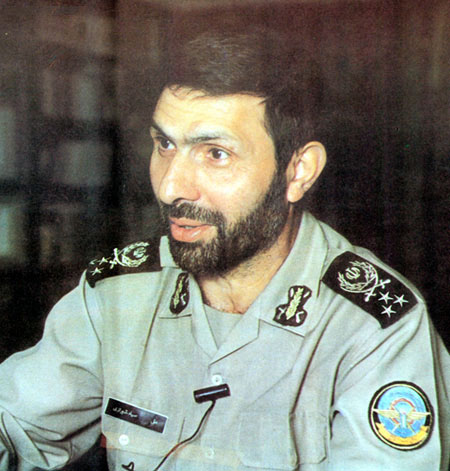

Artesh (Army) was led by Ali Shirazi (1981–88), who frequently commanded operations from the front. Roughly 70% of generals killed in action were IRGC; ≈ 30%, Artesh.

Courage Under Fire

For the liberation of Khorramshahr (24 May 1982), the leadership called upon its “best generals, who would fight like lions: Rahim Safavi, Hossein Kharrazi, and Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, all under twenty-five years old, but each in command of a division” (Pierre Razoux, The Iran-Iraq War, 215). Yahya Rahim Safavi headed IRGC operations (1981–88), and commanded IRGC from 1997. He aided the U.S. in the liberation of Afghanistan, for which Washington rewarded him with sanctions. Rezai appears on Iranian TV to discuss military affairs. Ghalibaf is Speaker of Parliament (majlis). Hossein Kharrazi, who deserted the Shah’s army, exemplifies courage and leadership in the Iran-Iraq War. Despite losing an arm in an earlier offensive, he led the Karbala-5 operation (“Battle of Basra”; 1987) and was killed when an Iraqi mortar shell exploded beside him.

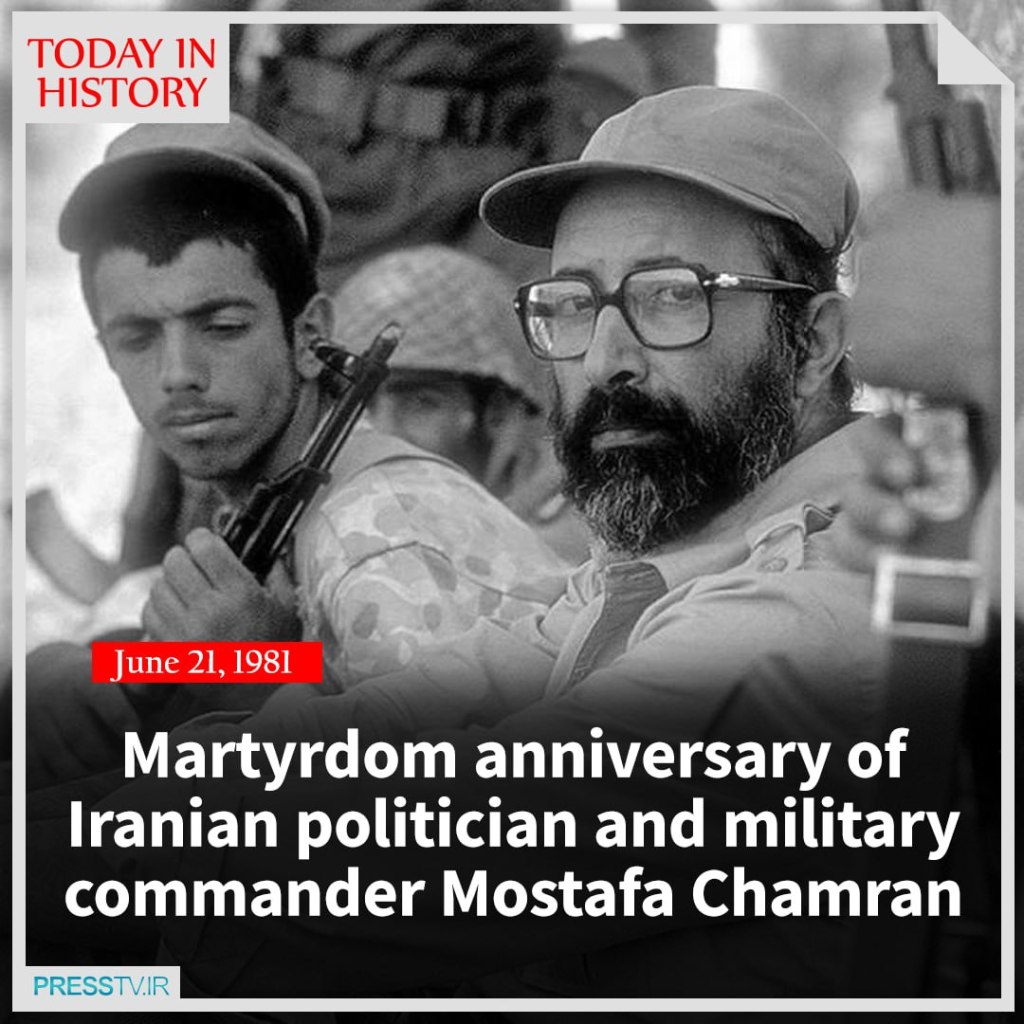

The generals were not fanatics. They were nationalistic and patriotic; most were well-educated, or like U.S. veterans, continued their education after the war. Mustafa Chamran may not typify the generation, but reflects its depth. Born in Iran (1932), he was educated in the U.S., earning a Ph.D. in electrical engineering at UC/Berkeley. Chamran heard “the call” and returned to Iran in 1979. He became Minister of Defense (1979–81), wounded in action, and died in a plane crash while returning from the front.

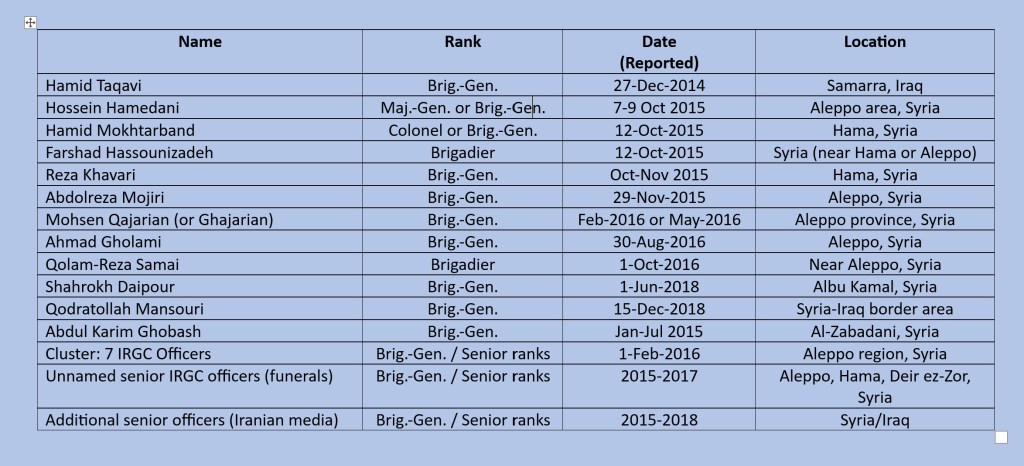

Iranian frontline leadership ethos continued after the “Imposed War.” Qasem Suleimani (murdered by the U.S. in 2020) rose to prominence in the Iran-Iraq War, but promoted to Brig.-Gen. afterwards. He led the Quds Force (1998–2020). Suleimani “and the Quds Force were instrumental in the fight against [ISIS].” Videos of Hajj Qasem leading from the front, or mingling with IRGC men, Shiʿa militia, and Iraqi or Syrian civilians, are ubiquitous on Telegram and Aparat (Iran’s answer to censored YouTube). In contrast, American generals visiting Iraq and Afghanistan were draped in body armor and surrounded by a phalanx of bodyguards, with Reaper drones conducting overwatch. Fig. 4, below, identifies IRGC generals KIA in the four-year war against ISIS.

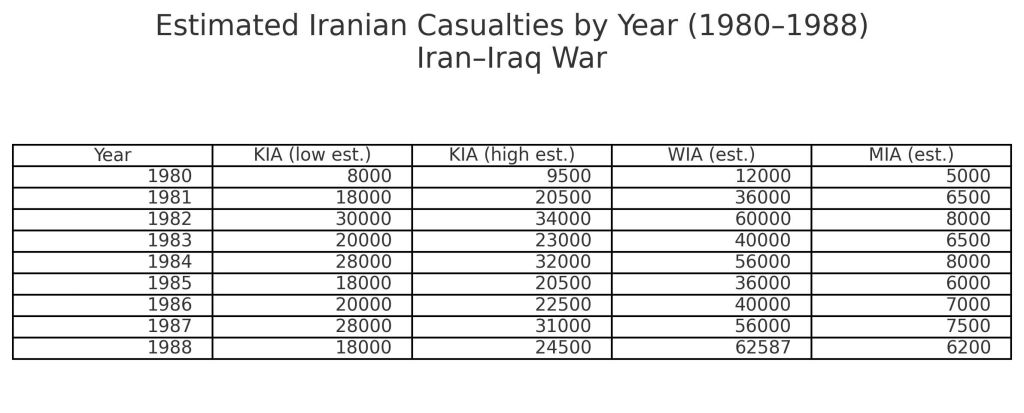

Iranian Casualties in the Iraq War

Iran has not published transparent, independently verifiable public datasets of year-by-year KIA, WIA, and MIA. There is no widely-accepted breakdown of casualties; datasets differ widely. I offer just best estimates. The most defensible KIA numbers: 188,000–217,000; WIA ≈ 398,000; ≈ 60,700 MIA (Fig. 1, above). They are compiled from diverse sources (e.g., veterans outlets, Martyrs Foundation, Islamic Republic). Regional “martyr lists,” of which there are many, were not accessed. The data utilized here are not dispositive.

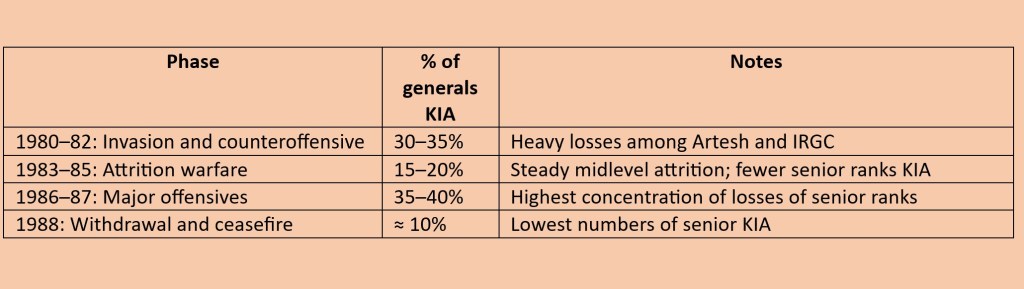

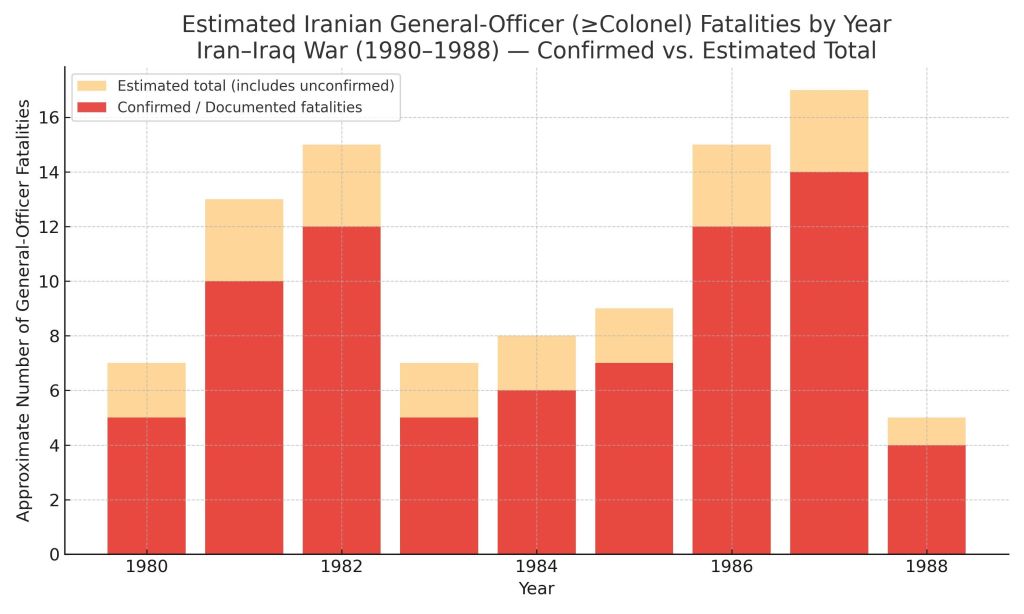

Annual distributions of KIA/MIA/WIA are estimates based on tempo; for example, 1980–82 witnessed high intensity war, but the tempo fell, 1983–85. Casualty trends track the four phases of the war (see Fig. 2). KIA numbers vary when a WIA later dies of injuries. This is true for soldiers who suffered injuries from Western-supplied chemical weapons.

Generals KIA in the Iran-Iraq War

Losses of Iranian generals range from 80–120; ≈100 is considered reasonable, and used in Fig. 3. Staff officer ranks are confusing because Iran has two Major-General ranks: Brig.-Gen. (sartip dowom; Brig.-Gen, 2nd class); Maj.-Gen. (sartip); Lt.-Gen. (sipahbad); Maj.-Gen. (sarlashkar; equivalent to U.S. four-star); Arteshbad (five-star equivalent; but there are none at present). The honorific “Commander” (sardar) is used in media when referring to IRGC generals, inadvertently obscuring the precise rank.

IRGC Generals KIA in Syria & Iraq Fighting ISIS

Frontline leadership was not limited to the Iran-Iraq War. In the 2014–18 period when ISIS surged in Iraq and Syria, IRGC led the resistance, supported by Lebanese, Iraqi, Syrian, and Afghan Shiʿa militias. The Shiʿa militias suffered heavy casualties. Iranian KIA estimates are 2,100–2,300, but IRGC casualties cannot be quantified because “Iranian nationals,” like civilians, are included in estimates. From published sources (Iranian media), we can glean that 15–25 senior IRGC officers were KIA in Iraq/Syria.

Iranian Generals Killed on 13 June 2025

On 13 June 2025, when Israel murdered Iranian generals (some while asleep in their beds, along with their families), the Iranian Armed Forces adapted and retaliated in hours. This is because (1) Iran has well-established succession protocols; (2) empowered subordinates to assume command; and (3) was accustomed to generals dying in wars.

The deaths of thirty generals from different service branches (see Appendix II) were felt professionally and personally in the Iranian government and military; but had negligible impact on continuity of command-and-control.

An astute commentator wrote, “Iranian military has truly shown ‘mission command’ and ‘empowered junior leadership.’ I don’t think American or Israeli military could have taken the losses of so many senior commanders and still struck back.”

Appendix I: Shiʿa “Martyrdom Complex”

Martyrdom discourse was central to military-public morale and propaganda during the Iran-Iraq War (Sept. 1980 to Aug. 1988). It continues to be a cultural framework for social-political cohesion and legitimacy. However, soldiers didn’t cheerfully charge into battle seeking a glorious death. Operational evidence demonstrates that during the eight-year war, the Armed Forces (Army: Artesh; and IRGC: Sipah or Pasdaran) emphasized training, intelligence, and combined arms tactics.

Western views that Iranians habitually engaged in martyrdom operations are generalized from early events during the war when IRGC and Basij (“volunteers”) engaged in infantry assaults with minimal armor and artillery support (e.g., operations in Nov. 1981, Mar. 1982, Apr.–May 1982). These were light-infantry assaults, not suicide charges. A sensationalized aspect is the sacrifice of teenagers with the Basij. Islamist terrorist organizations like ISIS and al-Qaida, known for suicide bombings and bloodcurdling martyrdom videos, shaped western interpretations of Islam and martyrdom.

Westerners also forget that Iran is multi-ethnic and multi-confessional. Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians, and Sunnis valiantly served in the Armed Forces; they did not subscribe to a Shiʿa “martyrdom complex.” They fought for their homeland. Sunnis that I interviewed for my book, The Sufi Saint of Jam: History, Religion, and Politics of a Sunni Shrine in Shiʿ Iran, proudly recall their service in the “Imposed War.” Iran’s non-Muslims and Sunnis continue to serve in Artesh, whereas Sipah retains its Shiʿa roots.

Narratives by Iranian veterans, and histories based on oral narratives and documents, reflect concerns among Iranian soldiers not unlike the concerns of soldiers in war: fear, exhaustion, emotional stress, sadness at the loss of comrades, desire to survive, etc. Shiʿa and Iranian culture, in essence, embrace the sacrifice of soldiers, and “wrap and bowtie” their deaths in the rhetoric of martyrdom.

An excellent resource is Annie Tracy Samuel, The Unfinished History of the Iran-Iraq War: Faith, Firepower, and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022), especially Chapter 9: “Faith and Firepower: Iran’s Prosecution of the Iran–Iraq War.” She utilizes Persian-language records at the IRGC’s “Holy Defense Research and Documentation Center.” Another source, despite the warts, is Pierre Razoux, The Iran-Iraq War (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2015).

Appendix II: Generals Killed in the Twelve-Day War

Not all of the generals named below were killed on 13 June 2025. The men who died on 13 June were not of “insignificant” office; yet, succession protocols were swiftly initiated, and in roughly eight hours, Iran launched the first wave of multiple retaliatory strikes:

1. Commander of the IRGC, Lt.-Gen. Hossein Salami

2. Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces, Lt.-Gen. Mohammad Hossein Bagheri

3. Commander of the Central Headquarters of Khatam al-Anbiya Base, Lt.-Gen. Gholam Ali Rashid

4. Commander of Khatam al-Anbiya, Lt.-Gen. Gholam Ali Rashid

5. Deputy Chief of the Operations Department of the General Staff of the Armed Forces, Brig.-Gen. Mehdi Rabbani

6. Deputy Chief of the Intelligence Department of the General Staff of the Armed Forces, Maj.-Gen. Gholamreza Mehrabi

7. Head of the IRGC Intelligence, Maj.-Gen. Mohammad Kazemi

8. Deputy head of the IRGC Intelligence, Maj.-Gen. Mohsen Bagheri

9. Deputy head of the IRGC Intelligence, Brig.-Gen. Hassan Mohaqeq

10. Deputy Inspector General of Khatam al-Anbiya, Maj.-Gen. Mohammad Jafar Asadi

11. Representative of the Commander in the IRGC Intelligence, Maj.-Gen. Mohammad Reza Nasir Baghban

12. Head of the IRGC Commander’s Office, Brig.-Gen. Masoud Shanei

13. Commander of the IRGC Aerospace Forces, IRGC Maj.-Gen. Amir-Ali Hajizadeh

14. Dep. Cmdr. of the IRGC Aerospace Forces, Brig.-Gen. Amir Pourjodaki

15. Deputy Chief of Intelligence of the IRGC Aerospace Forces, Brig.-Gen. Khosrow Hassani

16. Commander of the IRGC Air Defense Forces, Brig.-Gen. Davud Sheikhyan

17. Commander of the IRGC Aerospace Forces UAV unit, Brig.-Gen. Mohammad Baqer Taherpour

18. Commander of the IRGC Aerospace Forces in Tehran, Brig.-Gen. Mansour Safarpour

19. Brig.-Gen. Masoud Tayeb of the IRGC VKS (Military Space Force)

20. Brig.-Gen. Javad Jarsara IRGC VKS (Military Space Force)

21. Head of the Palestinian department of the 7th Al-Quds Corps of the IRGC, Brig.-Gen. Mohammad Said Izadi

22. Commander of the IRGC Al-Quds Force Unit 190, Brig.-Gen. Behnam Shahriari

23. Head of the Defence Innovation and Research Organisation (SPND) Maj.-Gen. Amir Mozaffarinia

24. Commander of the intelligence service of the IRGC’s Basij paramilitary, Brig.-Gen. Mohammad Taqi Yousefvand

25. Dep. Cmdr. of the IRGC’s Basij paramilitary for social affairs, [?]-General Meysam Rizwanpour

26. Chief of Staff of the IRGC in Alborz Province, Brig.-Gen. Seyed Mojtaba Moeinpour

27. Dep. Cmdr. of the IRGC in Alborz Province, Brig.-Gen. Mojtaba Karami

28. Dep. Cmdr. of the IRGC in Alborz Province for Social Affairs, Brig.-Gen. Akbar Enayati

29. Chief of the Police Intelligence Organization (SAFA) [?]-General Alireza Lotfi

30. Deputy Chief of Logistics and Support for the Southwestern Regional Headquarters of the Ground Forces, Brig.-Gen. Abbas Nuri.

You must be logged in to post a comment.